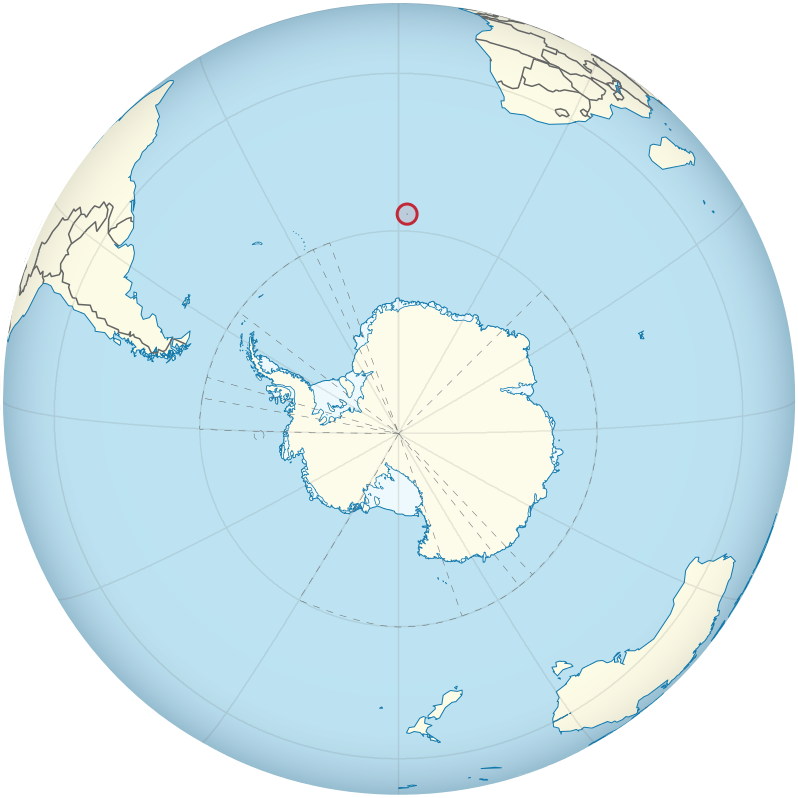

Bouvet Island: The Most Remote Island On Earth

The views are stunning, the weather is dodgy, and the nightlife is rubbish. But, if you want to be isolated, Bouvet Island is your best bet.

Bouvet Island is a Norwegian territory as far from any land as it is possible to be. Although uninhabited, many humans have now ventured to its shores and returned to tell the tale with photos in tow.

The island lies 1,600 miles from the coast of South Africa and around 1,100 miles north of the Princess Astrid Coast of Queen Maud Land, Antarctica.

So, the nearest land mass to Bouvet Island is as far as London is from Riga, Latvia. And even if you reached it, there’s not a whole lot going on in Queen Maud Land. There are no full-time residents – just an average of 40 researchers eking out an existence in the name of science.

If you swam a little further and reached South Africa (roughly the distance from London to Moscow) your first point of call might be somewhere near Cape Town – you’ll find more action there, but that’s a hell of a swim.

The island is just a speck of rock – 49 square kilometers; more than 90% of it is covered by a glacier and the centre is a huge deceased volcano. As far as temperatures go, the average annual high is 1.2°C and the average low is -2.2°C.

Bouvet Island is difficult to land on. Its ragged crust rises unsympathetically from every rugged corner.

A rock slide in the 1950s created a slope on the north of the island, called Nyrøysa, which offers the easiest point of embarkment, and now houses a weather station.

The island is named after Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier who first spotted it in January 1739. He was on the hunt for a large southern land mass and assumed Bouvet Island was part of it. At the time he was unable to navigate around it, so was unaware that it was an island. He named it Cap de la Circoncision.

When de Lozier marked this new land on a map, he charted the coordinates inaccurately; consequently, when it was next seen in 1808 by the whaler James Lindsay, it was thought to be a new sighting and named Lindsay Island.

In 1825, George Norris once again spotted the ice encrusted scrap of land and claimed it for the British Crown, it was renamed Liverpool Island.

Interestingly, Norris reported that his Liverpool Island was close to another island, which he dubbed Thompson Island. Thompson Island turned out to be a “phantom island” – in other words, it was later found to not exist and was removed from maps in the 1940s.

For a while, scientists believed that Thompson Island could have disappeared following some kind of seismic jiggery-pokery, but oceanographers have since noted that the sea is thousands of meters deep at that point, so who knows what Norris was going on about.

Norris could not land on Liverpool Island, but did dredge the seabed for geological samples.

Benjamin Morrell claimed to be the first man to land on Bouvet Island, where he reported slaughtering no less than 196 seals. His claim, however, has been questioned.

In Morrell’s ghost-written memoirs, he told a whole host of tall tales that experts have since refuted. Although he did manage a great deal of sailing and discovery during his life time, most researchers believe that his pants were, quite frequently, on fire.

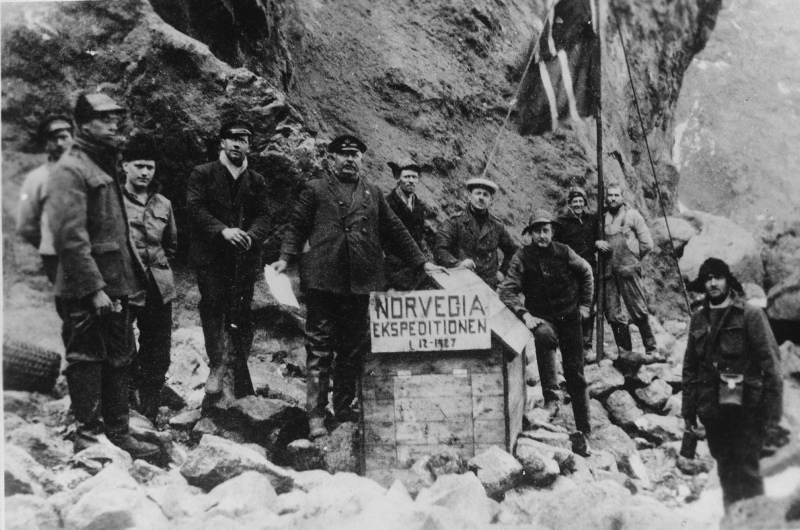

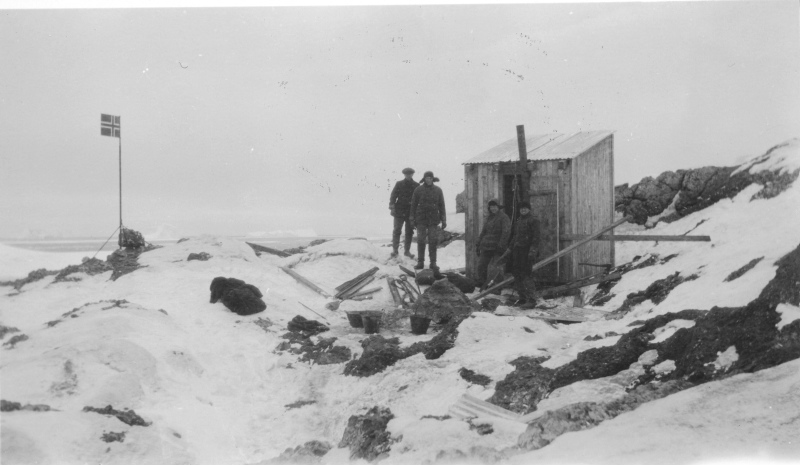

The earliest official landing on the island was by the Norvegia expedition; they set foot on the island in 1927. On the 1st of December, the expedition, led by Harald Horntvedt, claimed the island for Norway and named it Bouvetøya, or Bouvet. A small hut was erected and geological surveys were carried out.

(If the name “Bouvetøya” seems strangely familiar to you, it might be because it was the setting for the Alien vs. Predator movie.)

When the UK caught wind of Norway’s claim, they kicked up a bit of a fuss, saying that Norris had already baggsied Bouvet for the Brits; but, seeing as Norris had basically hallucinated a neighbouring island, their claim was weakened. In November 1929, after negotiations, Britain decided to let Norway keep the useless frozen stump of land.

In 1971, Norway made Bouvet Island a nature reserve to protect the wealth of marine life that live on and around the icy rock.

There are thought to be around 70,000 fur seals on the island, among other seal species. In the 70s, there were estimated to be 117,000 breeding penguin pairs and an extensive range of other seabirds.

Because of the island’s inclement weather and lack of flora, mammalian predators simply do not exist on Bouvet Island. Its distance from the meddling fingers of man is likely to keep these creatures well protected, too.

In March 1985, the weather was sufficiently good that the first aerial photographs of the entire island could be made, leading to the creation of the first accurate map of the island – 247 years after its discovery.

A research center was established on the island in 1996, but in 2006, an earthquake caused the building to disappear into the ocean below.

A new station was set up in 2014 with room for six people to stay for 2-4 months at a time.

No, it’s not really a holiday destination.

MORE FROM PLANET EARTH:

INCREDIBLE GLOBAL TEMPERATURE RECORDS

VIDEOS OF LIGHTNING UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL

“THE BLOB:” A METEOROLOGICAL MYSTERY