Most Accurate Coloured Model Of A Dinosaur Unveiled

The colour and pattern of an animal is no accident, it helps them avoid being killed, or, conversely, helps them to hide in order to kill something else. New research into the coloring of Psittacosaurus shows that “countershading” has been helping animals hide for millions of years.

A fossilised skeleton of a Psittacosaurus has recently given up some colourful secrets. The skeleton, unearthed in China, was covered in what paleontologists thought were dead bacteria within fossilised feathers. On further inspection, they turned out to be melanosomes.

Melanosomes create and transport pigment in animal’s skin and feathers. They are the most common light-absorbing pigment in the animal kingdom.

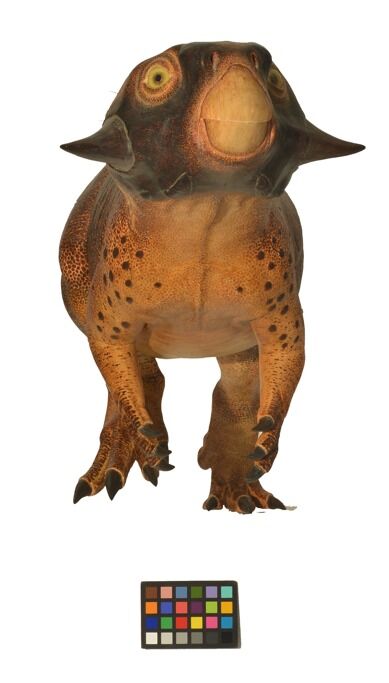

This discovery on the bones of the Psittacosaurus (meaning “parrot lizard”) allowed researchers at the University of Bristol to reconstruct the shading pattern on the long-dead animal. According to the paper, published this week in Current Biology, their findings have allowed scientists to build the most accurate reconstruction of a dinosaur to date.

Over the years, reconstructions of dinosaurs have taken a wonderful array of forms because, obviously, adding flesh, skin/feathers and colour to an ancient, partially crushed skeleton is a tricky job. There’s a lot of guesswork and a liberal dose of artistic license.

The Bristol team, with access to the most comprehensive coloring data ever found, have managed the best possible job. They enlisted Bob Nicholls, a top notch paleoartist, to help them construct this long-dead weirdo.

I say “weirdo,” because he was an odd-looking creature. According to Innes Cuthill, one of the researchers, Psittacosaurus was “both weird and cute” with horns on either side of its head and a tail covered in bristles.

Jakob Vinther, another of the researchers involved in the study, said of the results:

“The fossil preserves clear countershading, which has been shown to function by counter-illuminating shadows on a body, thus making an animal appear optically flat to the eye of the beholder.”

This countershading infers that this particular Psittacosaurus probably lived in a forested environment with a heavy canopy.

“Countershading” refers to coloring which is darker on the top of the animal and lighter underneath. The fact that countershading was used by these ancient beasties means that its predators probably used shadows to determine the shape of things, as modern humans (and other mammals) do today.

Read more: Camouflage in the natural world is a varied and incredible thing.

The Importance of Countershading

Countershading is so ubiquitous in nature that it’s easy to have never really noticed it. A myriad of species use the technique to throw off predators. For instance, if a predator is coming in from above, a fish that is dark on top will blend in with the blackness of the depths, and, if a predator is approaching from below, the fish’s lighter tummy will blend in more with the sunlit water’s above.

Of course, this technique works just as well if you are a predatory fish stalking your prey.

There is more to countershading than this, though. Many scientists believe it helps to interfere with animal’s perception. For instance, if you shine a light onto the top of a sphere, the top appears bright, whilst the underparts look darker. We use these natural shading patterns to determine that a shape is solid.

Now, if an animal colors itself so that the bottom is lighter and the top is darker, this helps to counteract the natural lighting, making the animal slightly less easy to detect.

This countershading technique is reversed in animals who wish to become more conspicuous, as an example, skunks are keen to make predators aware of their presence and remind them how foul their aroma is. The honey badger below has reversed countershading; he is reminding everyone else that he is a total nutter and should not be messed with:

You could be forgiven for thinking that this gentle trick of the light would be too subtle to be of much use in the wild. However, in nature, even the slightest bit of help can be the difference between life and death. At the end of the day, if a tiny switcheroo in coloration puts off your death for long enough for you to procreate, it is worth doing.

The fact that countershading is found in mammals, reptiles, birds, fish, insects and dinosaurs, means it must be doing something well enough to merit being conserved.

Thayers Law

Countershading in nature is also referred to as Thayer’s Law after the naturalist and painter – Abbott Handerson Thayer – who first noted countershading and had a good old think about it. In his book, Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom, published in 1909, he wrote:

“Animals are painted by Nature darkest on those parts which tend to be most lighted by the sky’s light, and vice versa. … the fact that a vast majority of creatures of the whole animal kingdom wear this gradation, developed to an exquisitely minute degree, and are famous for being hard to see in their homes, speaks for itself.”

There are still things to be learned about why so many animals choose this particular paint job, but its sheer prevalence means it must be important somehow. Not everyone is convinced about the common theory of how countershading works, so we’ll have to wait for more evidence before we get the full explanation.

For me, though, the most amazing thing about this story is that we now have a good idea of what an individual creature looked like as it roamed through the undergrowth more than 100 million years ago.

MORE DINOSAUR WONDERS:

NYCTOSAURUS – STRANGEST DINOSAUR EVER?

BEAUTIFUL EXAMPLES OF PALEOART

FOUR-WINGED DINOSAUR UNEARTHED IN CHINA