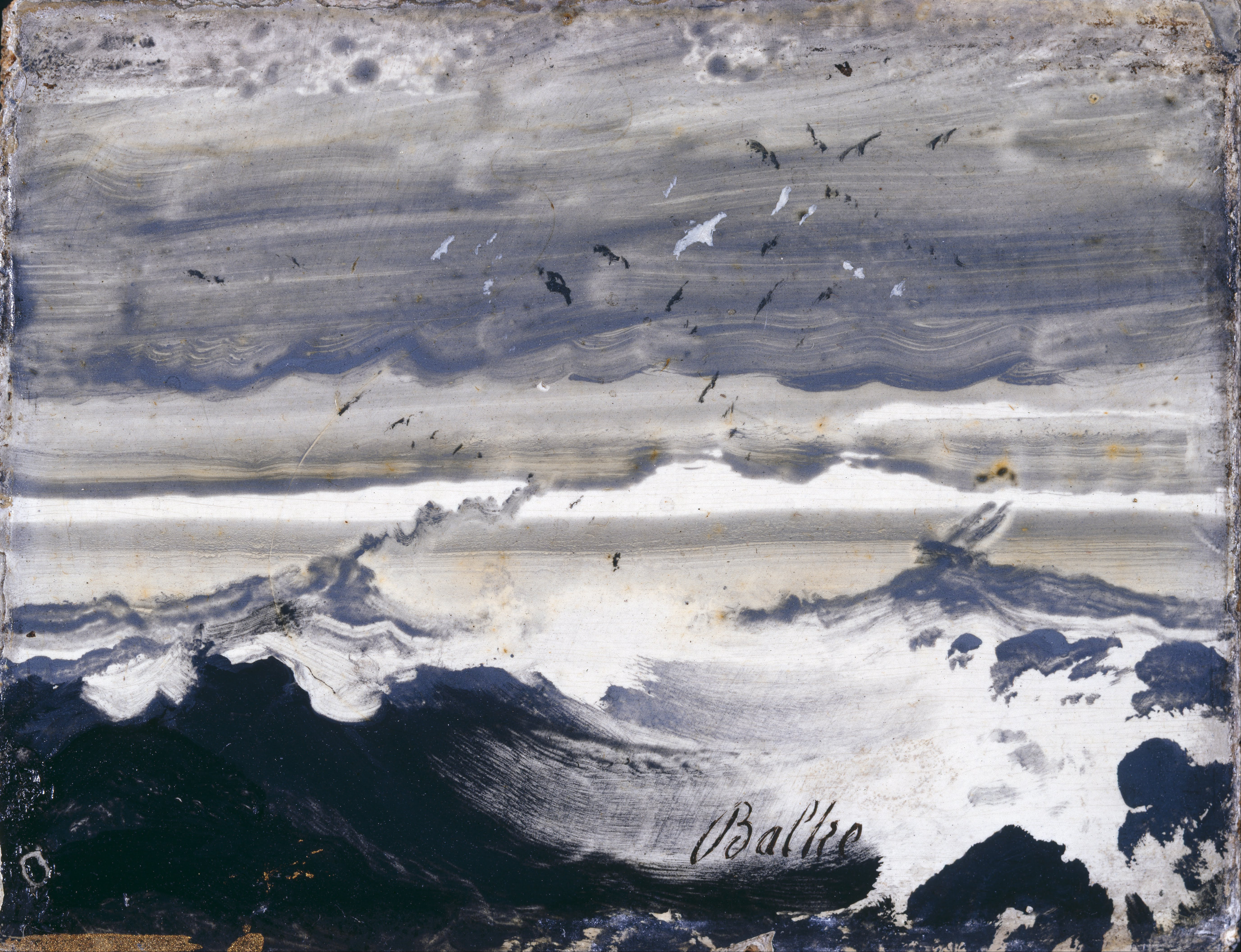

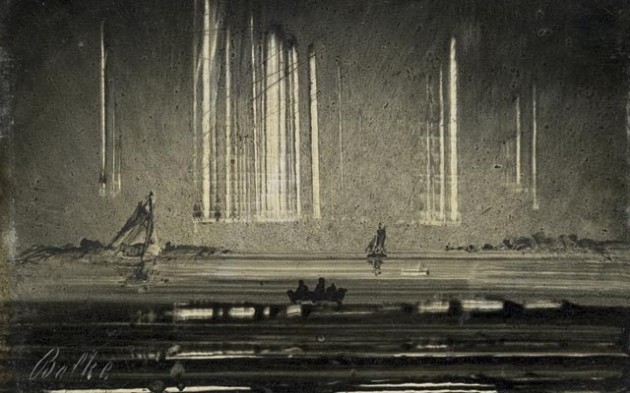

Peder Balke: A Bleak Norwegian Master

Peder Balke (1804-1887) painted the bleakest most impressive parts of one of Europe’s bleakest and most impressive countries. Famous in Norway for his romantic visions, he has largely been ignored outside of his home country.

Balke was born on the island of Helgøya, the largest freshwater island in Norway before moving to Ringsaker, on the mainland, and then to Toten, where he spent his formative years, just across the water from the island where he was born.

He spent his youth in a farming community where his painting was supported and encouraged by the locals who paid for his education; in return, he painted their farms.

Balke served as an apprentice to the Danish decorator and artist Jens Funch, he was later a pupil of Carl Johan Fahlcrantz, a Swedish landscape artist and then of Johan Christian Dahl (often described as “the father of Norwegian landscape painting”) from 1843 to 1844.

In the autumn of 1830, in his mid-20s, Balke went on an epic trek, sketching and painting as he went. He travelled from Telemark to Bergen and back to Hallingdal, a trip of some 1,000 miles through the wonderful natural drama of Norway. Once he returned, he turned his sketches and memories into works of art.

It seems that Balke was one of the first Norwegian artists to make a trip of this type and, according to him, he was overwhelmed by the:

“Opulent beauties of nature and locations delivered to the eye and the mind.”

His paintings beautifully measure this stark, breathtaking country and they were well received when he travelled through Europe; even Louis Philippe I of France decided to purchase one.

Balke was also a man with a social conscience. One of his biggest projects was the construction of the Balkeby, a wooden suburb of Oslo, built to provide safer, more pleasant homes for workers. Alongside the provision of a better life, he offered grants for artists and supported pensions for the elderly.

By the time Balke died, he was better known for his real estate development than his paintings; in fact, he had given up his career as a painter because the money he received just wasn’t cutting it. Despite finding royal patrons on his travels throughout Europe, he struggled to sell work in his homeland.

As is often the way, his work is, once again, finding favour further afield. The National Gallery displayed his work in 2014, making him only the third Scandinavian artist to receive such an honour; the gallery referred to him as:

“An artist who is only now being recognised as one of the forerunners of modernism.”

After Balke gave up his career as a painter, he still dabbled in the arts for his own pleasure. It is the paintings which he completed during this quieter phase of his life which have drawn the most critical acclaim. His colour pallet became more minimal and the washes lighter and more sparse. They have a real whiff of modernism about them as they drift away from pure Romanticism.

Some believe that during his trip to London he might have seen and been inspired by some of Turner’s works, but that can’t be known for sure; in any case, many want to keep his style as an emblem of Norwegian artistic innovation and I doubt they would be eager to secede influence to a lesser country such as our own.

Other critics see shades of Hokusai‘s Japan and even a whiff of 18th century Chinese prints. Balke was well-travelled, so he is likely to have come across both at some point.

Wherever he got his inspiration, the largest slab certainly came from the Norwegian wilderness. Take a look:

READ NEXT:

IVAN SHISHKIN’S BEAUTIFUL FOREST ART