The Magnificent Hoopoe: From Ancient Adulation To CBeebies

The hoopoe has charmed everyone from ancient Egyptians to the viewers of CBeebies. It’s an amazing species with some impressive quirks… the Estonians aren’t so keen on him though.

The hoopoe is a wonderful looking bird with one of the most pleasing of Latin names on earth: Upupa epops. There’s more to this guy than his snazzy hat and showy title, though.

The hoopoe lives across much of southern Europe and northern Africa, their colour scheme, fashion sense and general behaviour have earned them respect from societies both ancient and modern, carving themselves a special place in avian history.

The hoopoe is in the same clade as kingfishers, rollers and bee-eaters but they’re genetically lonely, being the last existing bird in the family Upupidae.

The hoopoe has distinctive black and white bands spread across its huge butterfly-like wings, and a long and gently curved black and brown bill; but it is his incredible headdress that really gets people’s attention.

The Secret Of The Hoopoe’s Success

The name “hoopoe” has two possible origins, it’s either a representation of the sound of their call, which is a kind of “oop-oop-oop,” or it could be from the French word “Huppée” which means crested.

The hoopoe are succesful and widespread, partly because they need very little from the environment to make themselves at home. Their basic requirements are flat ground without too much vegetation, so that they can dig around for insects, and vertical surfaces with cavities in to nest (rocks, walls, trees). That’s it really.

Hoopoe seem to be able to tolerate temperature extremes without too much problem. They are often found living peacefully in Sub-Saharan Africa but have also been spotted as far north as Alaska. Hoopoe don’t mind extremes of altitude either, one was recorded flying at about 6,400 m (21,000 ft) by the first Mount Everest expedition.

The hoopoe spends a lot of time digging in the dirt for snacks; they have particularly powerful muscles in their head and neck which allow them to open their bill whilst it is deep in the earth.

Farmers have considered these birds friends for as long as society has been farming because their diet consists of insects which farmers deem pests. This gets the hoopoe featured in the good books of any rural community.

The Hoopoe And Ancient Society

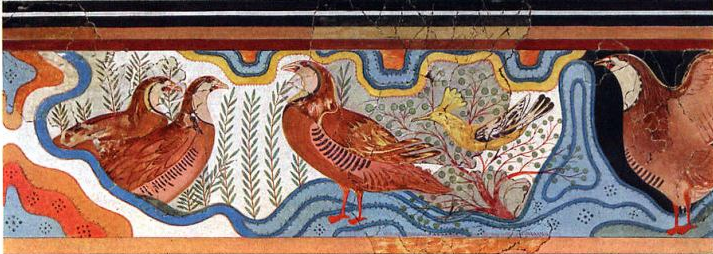

The hoopoe’s striking paint job, impressive crest, hard-wearing nature and pest eating penchant has given the birds a special place in society. In ancient Egyptian and Minoan societies paintings of hoopoe are to be found on the walls of tombs; they signified that the child was the heir and successor of his father.

This painting was found at the ancient Minoan site – Knossos, in Crete:

Egyptians would capture young hoopoes and keep them as pets. Even the child god Harpocrates is occasionally shown holding one. According to Horapollo (5th century BC) the hoopoe was renowned for being grateful towards its parents. Claudius Aelianus (around 200 CE) in On the Nature of Animals added that grown hoopoes were honoured for being doting parents, although neither he nor modern science has found this to be the case in any particular way.

The Egyptians even used a hoopoe hieroglyph, but to date its meaning is not clear. This image comes from comes from the mortuary temple of Userkaf (2494-2487 BC, first ruler of the 5th Dynasty), which is at Saqqara:

In the Torah, Leviticus and Deuteronomy, the hoopoe is listed as a bird that should not be eaten. The hoopoe gets a mention in the Quran too; Surah Al-Naml 27:20–22:

And he Solomon sought among the birds and said: How is it that I see not the hoopoe, or is he among the absent? I verily will punish him with hard punishment or I verily will slay him, or he verily shall bring me a plain excuse. But he [the hoopoe] was not long in coming, and he said: I have found out (a thing) that thou apprehendest not, and I come unto thee from Sheba with sure tidings.

Islamic literature states that a hoopoe saved Moses and the children of Israel from being crushed by Og (some kind of giant) after crossing the Red Sea.

The Hoopoe’s charms were not lost on the ancient Greeks or Persians either; they both considered the hoopoe the king of the birds. He gets special mention in Aristophanes’ The Birds, Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the ancient Persian book of poems – The Book of the Birds. In 2008 Israel chose the hoopoe as their national bird, pipping the white-spectacled bulbul to the post.

The Chinese Prince, scholar and artist Zhao Mengfu committed the hoopoe to bamboo (1254-1322):

Interestingly, if we step into northern Europe, the vibes that the hoopoe get from the locals are completely reversed. In Estonian culture, the hoopoe is linked to the underworld, and the sound of their call is thought to predict the death of either humans or herds of cattle. In Scandinavia, they are considered a sign of impending war. I guess you can’t please all of the people all of the time.

Hoopoe Physiology

The hoopoe’s eggs are kept in small holes in rocks or trees. As many as 12 eggs are laid in northern climes, where survival is less likely for the brood, and as few as 3 or 4 in warmer environs.

Another fascinating aspect of hoopoe physiology comes in a form of defence: they own a gland which releases a foul-smelling secretion akin to rotten flesh. The chicks rub this odorous liquid liberally across their young bodies and it is presumed to deter predators. The chicks are also adept at firing this substance with impressive accuracy should their nest get invaded. Perhaps this is why the animals were deemed by Leviticus to be non-kosher.

In more modern times the hoopoe has received an even mightier accolade in the British media. Can you think what it might be? I reckon some of you people reading this article, especially those with young kids, might have found the hoopoe’s shape familiar? Well, I will put your mind to bed. The hoopoe, albeit in a different colour scheme, is one of the “tittifers” who star in that creepy “In The Night Garden…” programme.

The hoopoe, charming as it is, continues to touch the human psyche as it has done for millennia, but in a slightly creepier way.

I’m assuming that, like me, you are now desperate to spot one of these fine feathered creatures for yourself. However, in the UK, they are just fleeting seasonal migrants. From April to May, on the south coast or in Norfolk you should spend some time hanging around golf courses, fields and dunes. You might be in luck, around 100 individuals are spotted yearly.

Despite the bird’s snazzy plumes, they are surprisingly hard to spot once they’re on the ground. So, happy hunting.

MORE BIRDS:

PEREGRINE FALCON: FASTEST CREATURE ALIVE

VIDEO OF A SNORING HUMMINGBIRD