Russia’s Prohibition Era: The Tsar’s 11 Year Alcohol Ban

When you hear the term “prohibition” you instantly assume it refers to the American ban on alcohol between 1920 and 1933. Of course, they aren’t the only country to have gone through a period of prohibition, or at least some kind of curtailment of booze.

Many Islamic countries have banned booze all together and others, like Norway, Denmark and the Czech Republic have tried to reduce the amount of drink sold, or at least minimise the strength of the booze it produces. Interestingly, in Venezuela there is a blanket ban on the sale of alcohol for 24 hours before a vote. They hope it minimises violence on the day. It’s bound to help, but I guess any rabble rouser worth his salt would simply stock up the day before.

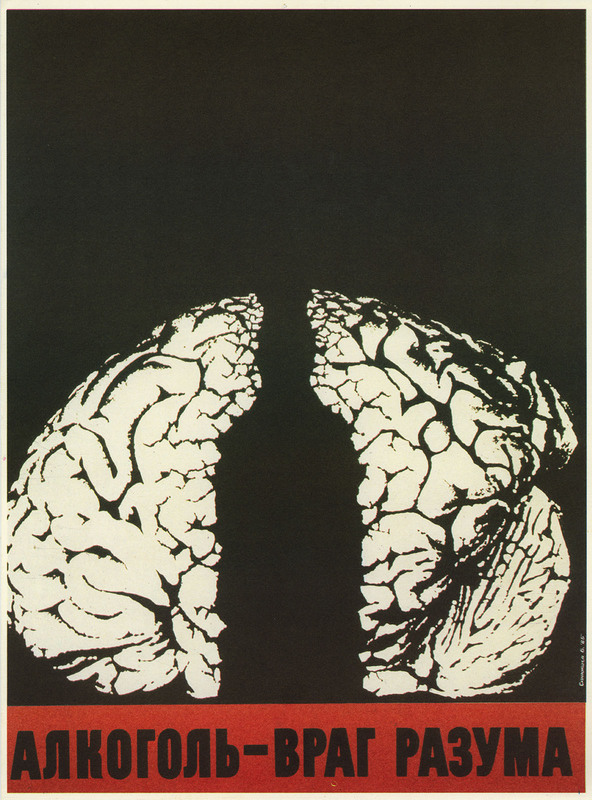

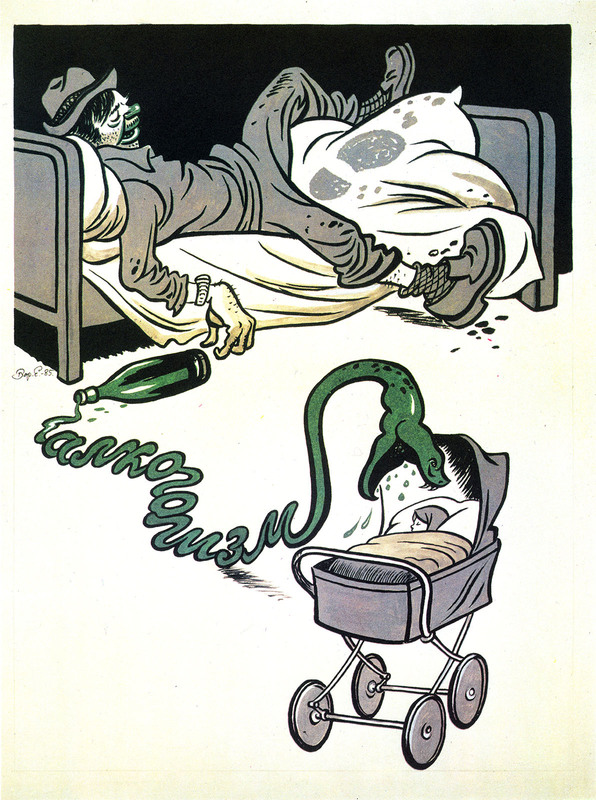

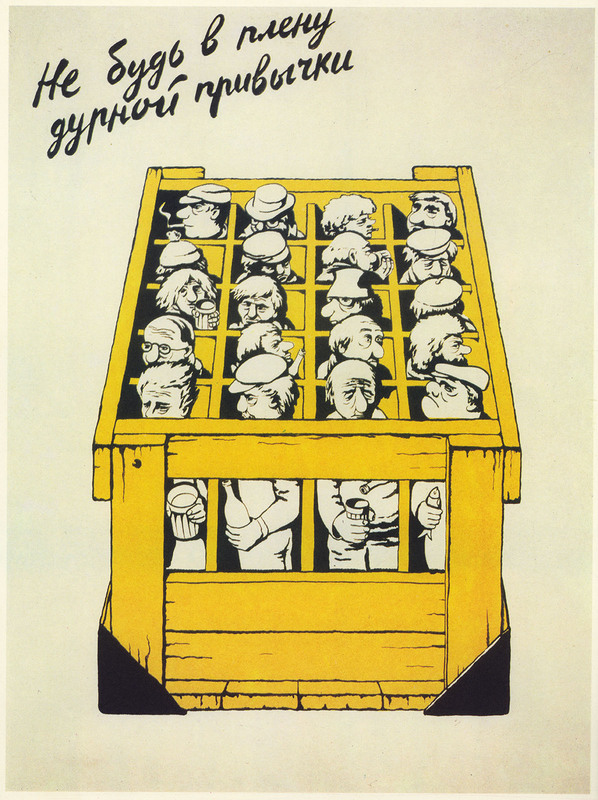

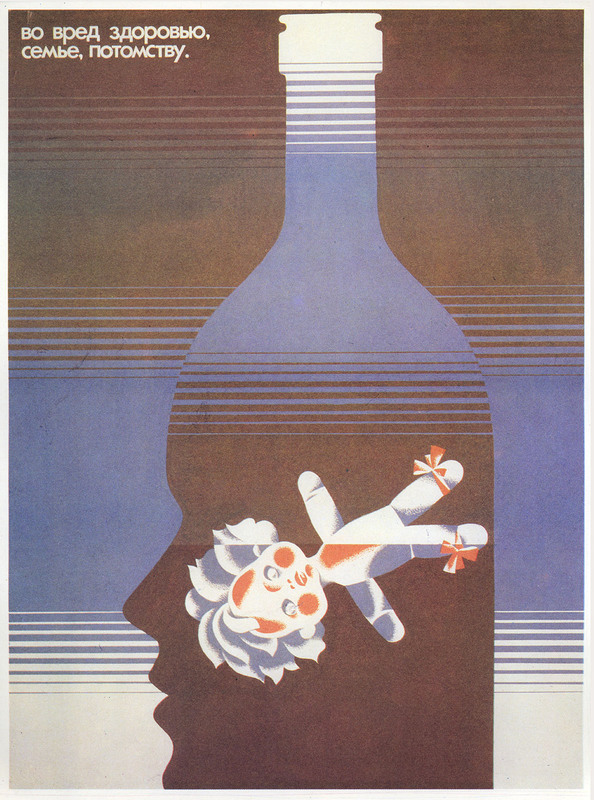

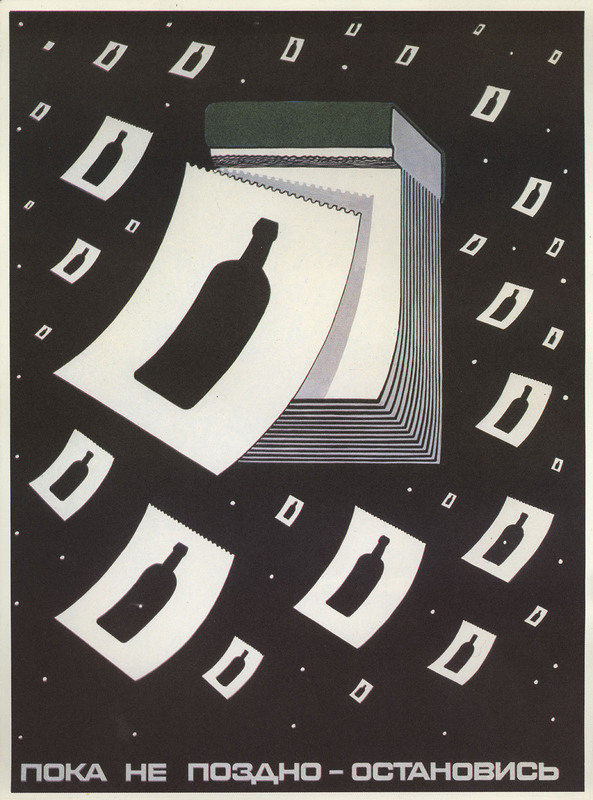

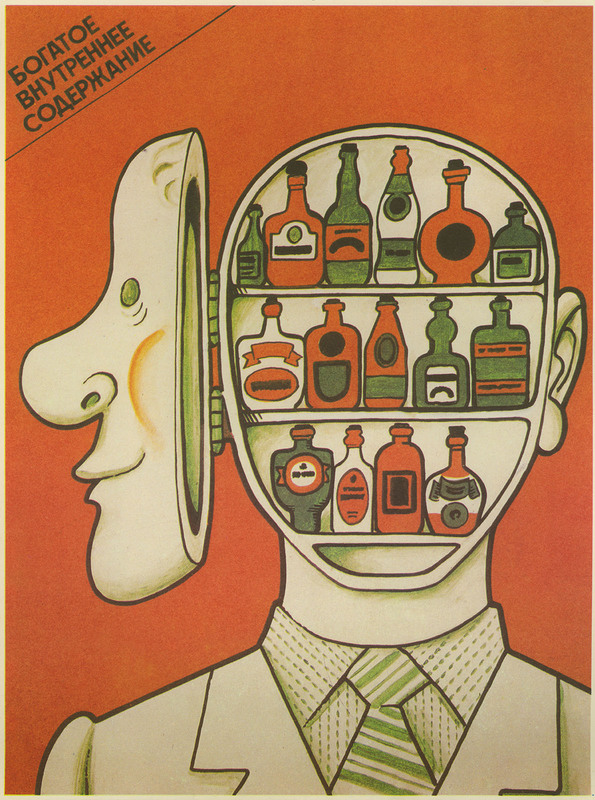

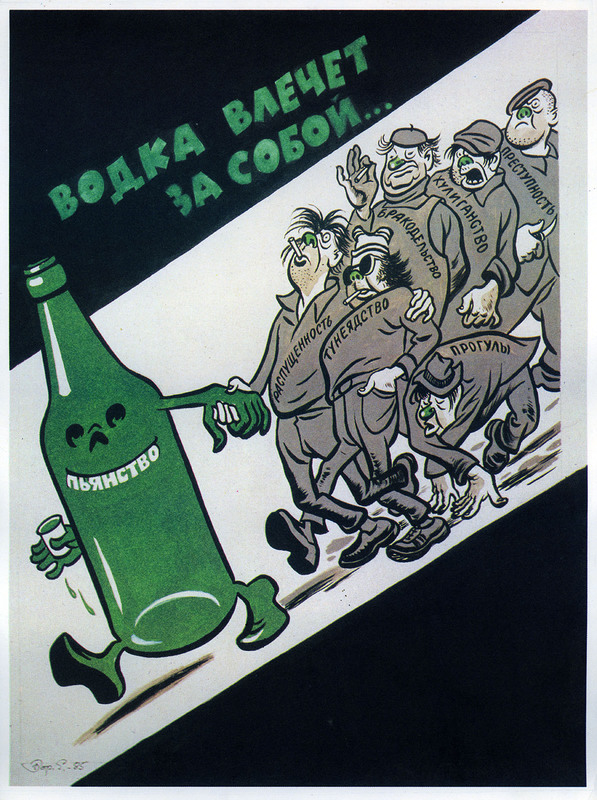

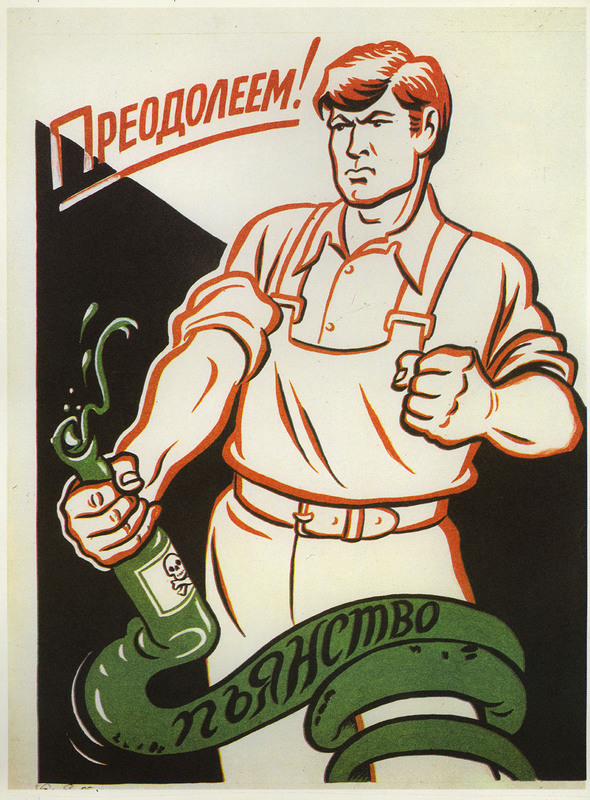

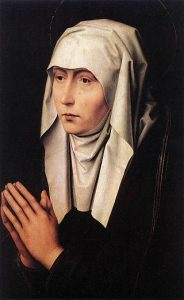

Russia is in fact one of the few non-Islamic countries to have trialled a (pretty much) complete ban on booze production and sale. Below are some facts and details about the Russian prohibition, mixed in with some Russian anti-alcohol posters from across the decades (mostly 50’s – 70’s I think).

It was the infamous Tsar Nicholas II who banned the production and sale of alcohol throughout his great lands. The prohibition began in 1914 and lasted an impressive 11 years, it even continued after the successes of the Bolshevik revolution and the eventual ousting of the Tsars.

Nicholas II had travelled through rural Russia and witnessed the alcohol-induced fallout after the Russo-Japanese war (1904-5). Alcohol based mental illness was rife and, during troop mobilisation, alcohol had hindered the war effort no end. He saw poverty, farms and businesses neglected, and he squarely blamed the booze.

The Tsar decided that, with an impending troop mobilisation for WWI, it would be a good idea to ban drink as soon as possible. So he did.

Although the Russian people didn’t drink a huge amount (much less than the Italians and French, for instance), when they did drink, it was always vodka, and it was always to huge excess.

The prohibition by the Tsar was a bold move, though. Roughly one-third of the government’s entire revenue came through the sale of vodka and there was a war on the horizon. British politician David Lloyd George described it:

…the single greatest act of national heroism.

As with any sweeping change to policy, there were positive and negative effects. Psychiatrist Ivan Vedensky and physiologist Alexander Mendelson carried out research during the ban; if they are to be believed, things improved greatly (for some). They reported a dramatic drop in crime, mental hospitals had virtually no patients left, and village life was, all of a sudden, wonderful.

Peasants were not only upgrading their farms, buying samovars (fancy kettles) and sewing machines, but they were also depositing spare money into savings. One peasant who was interviewed said:

Even domestic animals have become more cheerful.

One group of Russians who weren’t 100% happy with the changes were the medical students. Students were normally granted the bodies of people who had committed suicide. Now that alcohol wasn’t around to addle people’s minds and make them sour, the student’s supply of corpses literally dried up.

Prohibition was not welcomed by all. Any legislation of this size and scope was bound to cause some beefs somewhere along the line. Hardened booze hounds were hit worst and there was a definite increase in home brewing and the consumption of “surrogates” like varnish and polish. Also, weddings were an altogether different event without booze. Some enjoyed the fact that they were a darn sight cheaper when they were dry.

There were greater problems, though. In 1914 alone, 230 former drinking saloons were broken into and destroyed in desperation. On many occasions these wine riots required police to fire into the crowd to disperse them. Even conscripts were found breaking into wine cellars in a sober frenzy.

The Russian booze industry was a big employer, so another headache for the Tsar’s prohibition era was the 300,000 people who were now out of a job. They all needed to be paid from government coffers.

Alcohol production was forced underground. All villages, it seems, were making their own. From memoirs written at the time we find that nothing was too non-drinkable to get mashed up and drunk. Hooch ingredients included sawdust, shavings and mangel beets (a root vegetable meant for animal consumption) alongside the more obvious polish and varnish. On that note, polish and varnish sales increased ten fold.

As if that wasn’t enough to contend with, cocaine and heroin now entered the fray. They had both been available over the counter in Russian pharmacies before prohibition, but in these dark days their use really took off.

Finally, in 1925, Russia let the alcohol flood back in. They needed the income to modernise the country’s struggling economy. According to some accounts, when the flood gates were reopened, people were hugging and kissing on the street and crying with joy.

Over the following years there were other attempts to curb the amount of alcohol consumed by Russians (in 1958, 1972 and 1985 in particular), but no one was brave/stupid enough to risk the all-out ban again.

Here are a few more posters to round things off.

MORE FROM RETRO RUSSIA:

WEIRD OLD RUSSIAN FILM POSTERS