The History Of Life: The Devonian

Welcome to the fourth instalment of this brief foray into the birth and progression of life on earth. I started with the Cambrian, moved onto the Ordovician followed by the Silurian. Today we welcome the Devonian age which started with three mass extinction events at the end of the Silurian around 419 million years ago and shut up shop about 359 million years ago when the Carboniferous began.

The Devonian is named after the county of Devon where rocks from the era were first studied. The period saw the first significant adaptive radiation of life on terra firma, i.e. a rapid diversification of species.

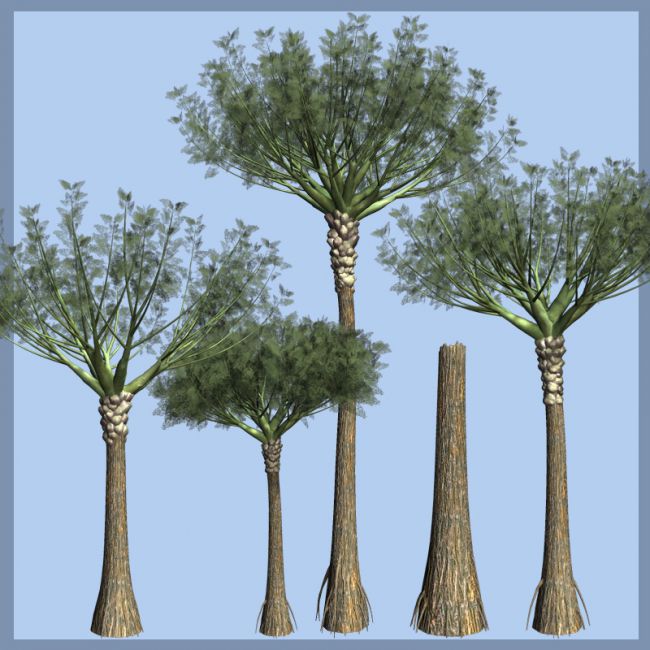

Plants that reproduce using spores – Pteridophytes – formed planet earth’s first forests and by the middle of the Devonian some plants had developed the first ever roots and leaves. By the end of the period the first seed-bearers had been born. The earliest known trees, from the genus Wattieza, appeared in the Late Devonian around 385 million years ago (pictured below). The rapid diversification of plants is sometimes referred to as the “Devonian Explosion”.

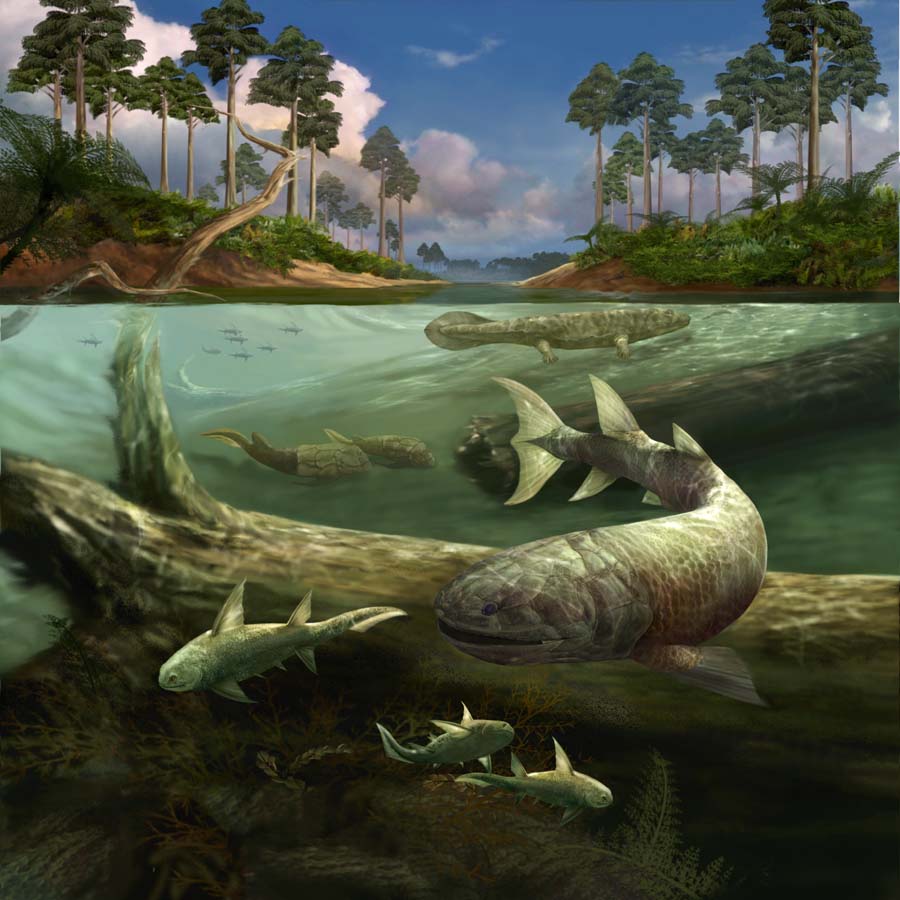

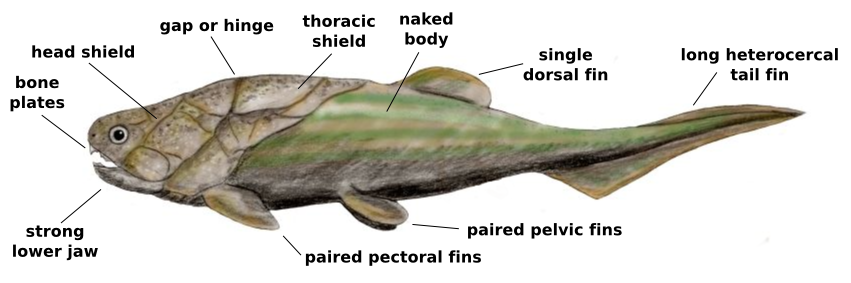

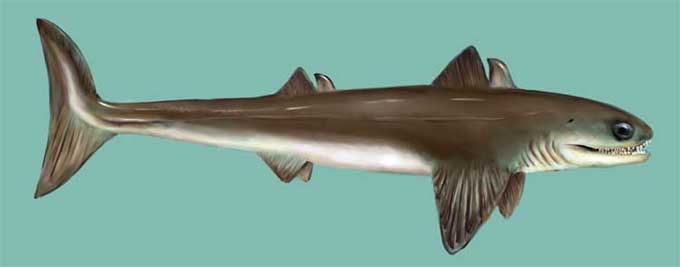

The Devonian is often called the “Age of Fish” thanks to its bewildering diversification of fish species. The first ray-finned and lobe-finned bony fish appeared, while the placoderms (now extinct armoured fish) began dominating almost every known aquatic environment. Sharks also had a hay day.

Significantly for us, the first, brave tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates) that made it onto land in the Silurian began evolving their strong fins into genuine bona fide legs.

Temperatures in the Devonian were relatively clement and there were probably no glaciers at all on the surface of our planet. Tropical sea surface temperatures were a balmy 30 degrees Celsius.

Throughout the Devonian CO2 levels dropped dramatically, in part due to the new forests that had arrived. As the plants died they drew carbon out of the atmosphere and laid it down as sediment. This drop in CO2 seems to have brought on a drop in temperature of around 5 degrees. As the Devonian drew past the mid-point, temperatures began to rise again (although CO2 levels do not) and by the end the temperature was similar to the point at which we joined it.

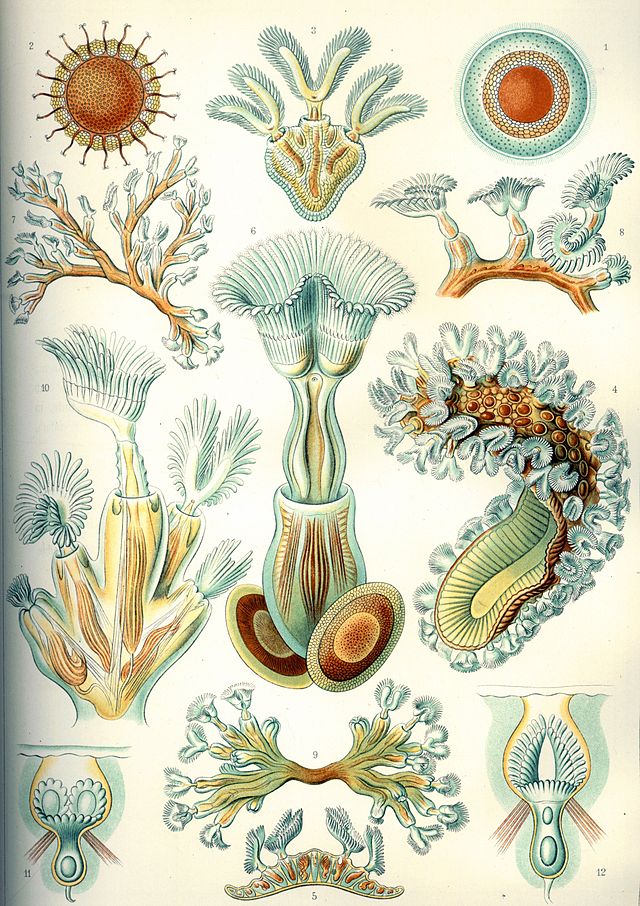

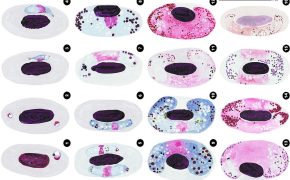

Life in the sea during the Devonian continued to be dominated by bryozoa, commonly known as moss animals. Here’s a drawing by Ernst Haeckel of some extant species of bryozoa:

(More from Ernst Haeckel here)

Brachiopods (like bivalve molluscs) increased in number, the enigmatic hederelloids (below) peaked in the Devonian as did microconchids (little wormy things) and corals.

Lily-like crinoids (they’re animals but they look like flowers) were abundant, and trilobites were still a common sight. As for vertebrates, jaw-less armoured fish (ostracoderms) declined in diversity, while the jawed fish (gnathostomes) increased in both the sea and fresh water. Armored placoderms were numerous during the lower stages of the Devonian Period and became extinct in the Late Devonian, maybe due to competition for food against all the newly evolved fish species.

Early cartilaginous (Chondrichthyes) and bony fishes (Osteichthyes) also become diverse and the first abundant genus of shark, Cladoselache, appeared in the oceans during the Devonian Period. Life on dry land evolved to include mites, scorpions and myriapods. It seems that the earliest insects may have also occurred around 416 million years ago in the early Devonian. The first amphibians made an appearance too.

Towards the end of the Devonian a huge extinction event wiped out nearly all of the agnathan fishes and a second pulse of extinction marked the end of the period. The extinction events of the Devonian were in fact more drastic than the more famous event that ended the Cretaceous.

It was the marine critters that suffered greatest, and of them the shallow warm-water dwellers were hit the worst. Luckily for use, land-dwelling tetrapods weren’t hit too badly at all. If they had been we might well have never come about in the first place.

No one knows what caused the Devonian extinction events, one theory is an asteroid impact; there certainly were large impacts around the right sort of time, but a suitably large crater to have caused such devastation is yet to be found. And the fact that life on earth was left pretty untouched points away from that explanation.

The Age of Fish ended with vast numbers of marine species disappearing for good. But on a lighter note, our first air-breathing relatives with legs took their first steps in the dry.

MORE PALEO STUFF: