The Hole: Russia’s Abandoned Mir Diamond Mine

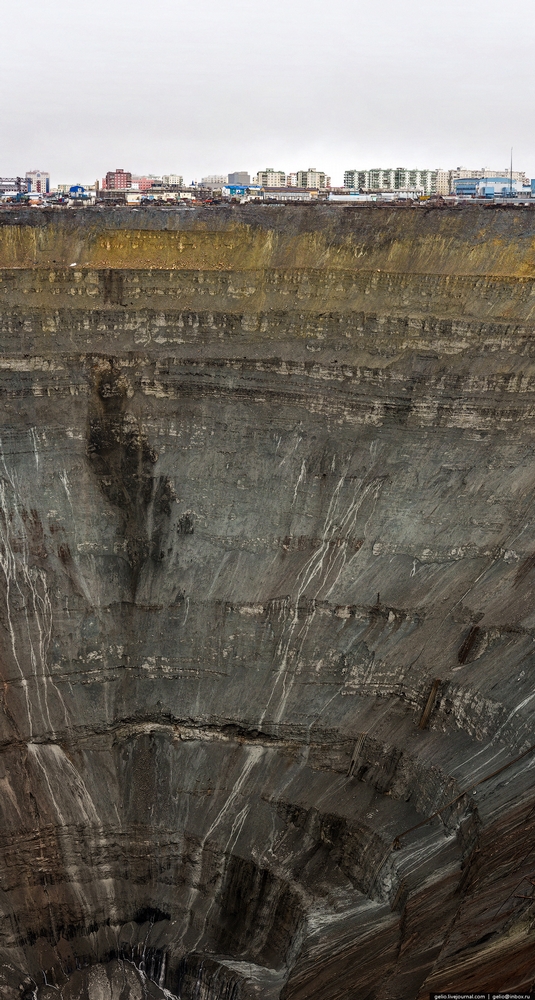

The Mir Mine (Кимберлитовая алмазная трубка) in Yakutia, Siberia is lovingly referred to as “The Hole;” it’s a dashingly impressive divot.

Surprisingly, this inactive diamond mine is only the second biggest man-made hole in the world (after Bingham Canyon Mine, Utah) but if you ask me, it’s the most impressive to look at.

This Siberian mine is 525 metres deep (1,722 feet) and 1,200 metres across (3,900 feet). To put that into perspective, if you balanced five Statues of Liberty or Big Bens on top of each other, they’d still not reach the rim.

Work on the mine started in 1957 in ridiculously harsh conditions. Seven months of winter a year made it almost impossible.

Their Siberian winter lows were so cold that car tyres would explode, steel would shatter and oil would freeze.

Workers had to thaw out the permafrost with jet engines and blast the earth with dynamite to reach the kimberlite below (kimberlite is a rock that often contains diamonds).

The summer months brought different problems: the earth turned to slush. Buildings surrounding the mine had to be built on piles so they didn’t sink into the gunk; the processing plant was constructed more than 20 km away on firmer ground.

Basically, Siberia is a nightmare to do any kind of sensible work in. So don’t bother.

The mine hit its peak action in the 1960s when it was pulling out 2,000 kg of diamonds a year.

In the swinging 60s, De Beers, the diamond scavenging megalomaniacs, were distributing more of the world’s diamonds than anyone else. As such, they took an obvious interest in this huge and lucrative Russian mine.

De Beer requested a visit in the 1970’s. The Russians begrudgingly accepted, but didn’t make things easy for the visitors.

In the summer of 1976 De Beers executive Philip Oppenheimer and chief geologist Barry Hawthorne arrived in Moscow. Soviet scientists held a series of lavish banquets and lengthy meetings to purposefully delay the visiting pair.

By the time they reached the Mir Mine they had just 20 minutes left of their visas and barely saw any of the mine and its workings.

But, what Oppenheimer and Hawthorne did see blew them away. The fact that water freezes in Yakutia winters means that the processing of the diamond ore was done without the use of water at all. The De Beer guys were dumbfounded by this.

The Hole operated for 44 years in total, finally closing its doors in 2004. Nowadays, diamonds are still being pulled from smaller mines, keeping the people in the region in work. The town that was built off the back off the mine is Mirny.

Around 70% of Mirny’s 37,000 population are employed in the diamond industry somewhere along the line. The town, which sprung up to house mine workers in the early days, still has diamond production at its heart.

It’s a pretty bleak place to live, though. Temperatures drop to -50 in the winter and the nearest town is 250km away. Isolation in the extreme.

The diamond company now in charge is Alrosa, and they still keep the population well looked after. The company funds affordable housing, hospitals and cultural centres for the people of Mirny. Alrosa also pay for occupants to fly to see family once every couple of years.

Interestingly, helicopter’s are banned from using Mirny airport due to the safety concerns of being right next to a massive hole.

Alrosa provides the regional government of Yakutia with about half of their yearly budget, so diamonds are still an essential part of the area’s economy.

Mirny sounds pretty bleak. I tried to find some Google street view images, but even Google Street Car hasn’t visited. However, on the town’s official site, there are loads of pictures and they seem like they have quite a nice time:

Still pretty bleak, though:

READ NEXT:

THE BIGGEST CUBIST STATUE IN THE WORLD