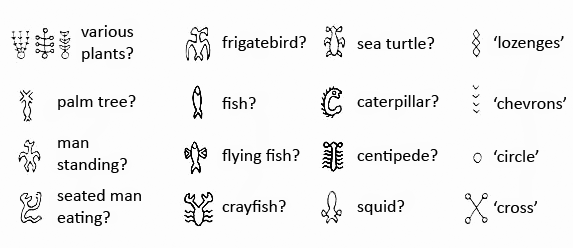

Rongorongo: The Most Mysterious Language In The World

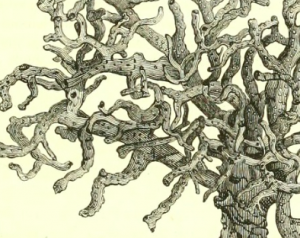

Easter Island is tiny and bewilderingly remote. The island’s residents – the Rapa Nui – are most famous for their incredible stone heads. They’re also well-known for being part of a civilisation that crumbled due to an influx of rats and rampant deforestation.

Despite the island’s small size, it houses more than its fair share of intrigue; one of its many mysteries is the lost language of Rongorongo.

Europeans first discovered the written language of Rongorongo on wooden tablets in the 19th century. Although many accept that the tablets contain a language, others are still unsure whether Rongorongo is technically a full blown language.

To date, no one has been able to decipher the glyphs despite numerous lengthy efforts. If the squiggles do turn out to be a bona fide language, they will be one of the very few examples of independent writing in human history.

It seems that there were only ever a small number of literate elite islanders capable of reading the inscriptions. These elite Easter Island priests and noblemen were all kidnapped during the Peruvian slave raids; most died shortly after from diseases, along with their knowledge of Rongorongo.

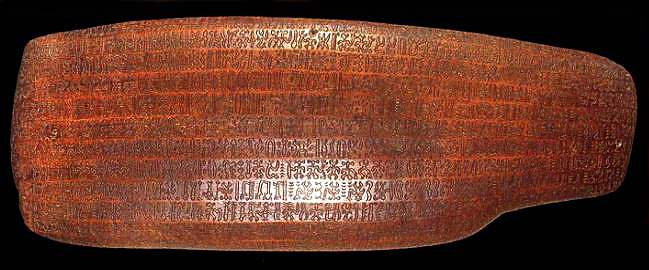

“Rongorongo G-r Small Santiago (raw)” by unknown – CEIPP, Nouveau regard sur l’Île de Pâques. Moana Editeur, Saintry-sur-Seine. 1982:126, via rongorongo.org. Licensed under Fair use via Wikipedia.

Dating of the wood that holds the glyphs has been tricky, but we know that in the 1700s when explorers were landing on Easter Island, there were no large trees left. So any of the tablets that came from large trees must, at least, predate that. In 1770, González de Ahedo wrote:

“Not a single tree is to be found capable of furnishing a plank so much as six inches in width.”

So, we can assume that Rongorongo was rife before then.

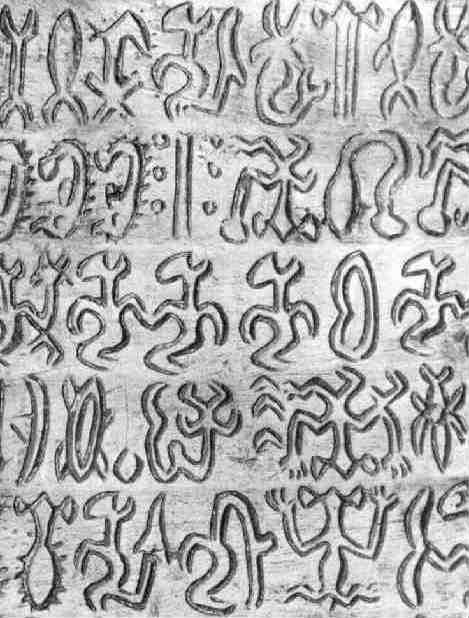

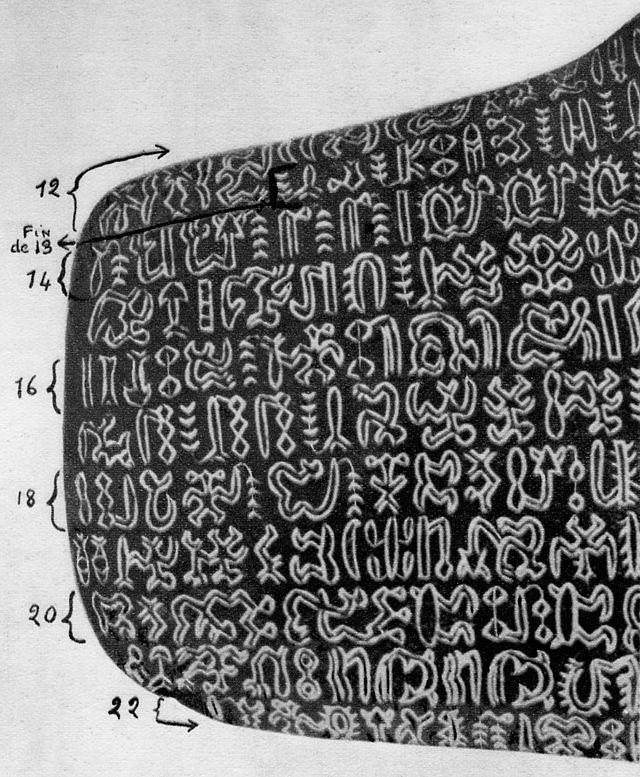

Interestingly, the language is written in alternating directions, a system called “reverse boustrophedon.” The reader begins at the bottom left-hand corner of a tablet, reads a line from left to right, then rotates the tablet 180 degrees to continue on the next line.

It seems that small obsidian flakes, or sharks teeth, were used to etch the Rongorongo glyphs into the medium of choice (mostly wood or stone).

The initial discovery of the Rongorongo glyphs was by an evangelical friar Eugène Eyraud who arrived in 1864; he planned to spend a few months teaching the inhabitants about the good book:

In every hut one finds wooden tablets or sticks covered in several sorts of hieroglyphic characters: They are depictions of animals unknown on the island, which the natives draw with sharp stones.

Each figure has its own name; but the scant attention they pay to these tablets leads me to think that these characters, remnants of some primitive writing, are now for them a habitual practice which they keep without seeking its meaning.

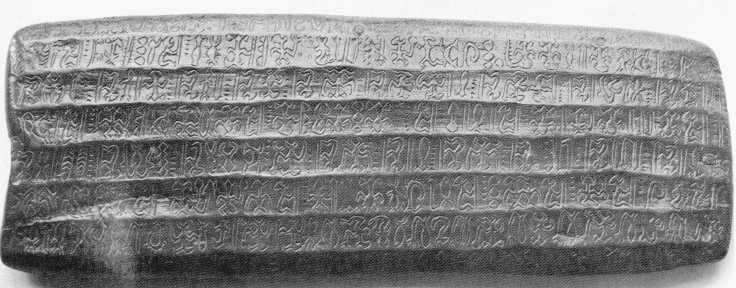

“Rongorongo B-v Aruku-Kurenga (end)” by Photograph from the Trocadero Museum (for GFDL, cite source above as old copyright holder) – Chauvet, Stéphen-Charles; on-line translation by Ann Altman (2004) [1935] L’île de Pâques et ses mystères (Easter Island and its Mysteries), Paris: Éditions Tel. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Just a few years later, the Bishop of Tahiti showed up on Easter Island. He found that, despite there having been hundreds of tablets just a few years earlier, virtually all of them were now gone.

What happened to them all? Well, it seems that the Easter Island residents saw no real purpose for them, they couldn’t read them after all, and wood was in short supply:

The Bishop questioned the Rapanui wise man, Ouroupano Hinapote, the son of the wise man Tekaki [who said that] he, himself, had begun the requisite studies and knew how to carve the characters with a small shark’s tooth.

He said that there was nobody left on the island who knew how to read the characters since the Peruvians had brought about the deaths of all the wise men and, thus, the pieces of wood were no longer of any interest to the natives who burned them as firewood or wound their fishing lines around them!

A. Pinart also saw some in 1877. [He] was not able to acquire these tablets because the natives were using them as reels for their fishing lines!

Sad isn’t it?

We may never know what the rongorongo tablets say but maybe they don’t say anything at all.

MORE LINGUISTIC STUFF:

THE MOST USELESS PHONETIC ALPHABET

SLANG TERMS FOR “HEAVY RAIN” IN OTHER LANGUAGES